Picture perfect office – © Dr. Michael WhiteKia Orana Everyone!Firstly, my apologies for being offline for a while.I’ve been extremely busy researching the rapid impacts of ocean warming on my atoll (9 South; 158 West).These include coral bleaching and death of our giant clams (Tridacna maxima).Also many of our trees have suffered badly and have either collapsed or are very sick.I’d like to thank my friends and research colleagues: Papa Ru Taime & John Beasley. Meitaki Poria.I’ll try and use this post as a form of blog and will deal with each aspect over the coming weeks.In particular I am now seeing secondary impacts, such as algal growth on the bleached corals ~ so in time this may cause a shift in fish populations or marine invertebrates.So this is truly the living, shifting face of climate change.Welcome to our new world!

Deeper corals suffered more than many surface ones, probably because deeper species have a narrower thermal range

The bleaching events mentioned above are so important that I wanted a quick publication to notify the international scientific community of this ecosystem impact. Usually the major sites, Great Barrier Reef for instance, get wide media coverage, but the remote places are rarely mentioned; if they are even studied, which many are not.

The editor of The Marine Biologist ~ Guy Baker ~ says you may share this PDF and the citation is below:

White M (2016) Too hot in Paradise! The Marine Biologist, April 2016: 26-27. Published by the Marine Biological Association https://www.mba.ac.uk/marinebiologist/

TMB_Issue6_TooHotInParadise.pdf

I hear that death and bleaching of corals in hotter (warmer?) tropical waters is due formation of hydrogen peroxide by combination of nascent oxygen with seawater. H2O2 is a wound cleaning germ killer everyone knows, detrimental to the lower forms of life. Bleaching of corals does definitely indicate more damage to the basic structure of the entire than as seen in isolation. Death of Tridacna maxima in the Andamans, I believe, is due to sudden flush of H2O2. What’s your idea Mike?

A typo: should read -entire “ecosystem “

Thanks Krishnan, in the PDF I wrote of ‘free oxygen radicals’ becoming toxic to the corals & clams. Reading the link below this tallies with your comment on hydrogen peroxide. I’m uncertain if the compound is the trigger or the result: but in either case the animals would not want ‘bleach’ on their skin and so it is sloughed off rapidly. Also explains why bleaching happens so quickly. Mike

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/hydrogen_peroxide#section=Top

Thanks Mike for informing us about both your work, and the fate of corals around your Atoll. Indeed it is getting not only too hot in some parts of paradise, and too dirty in others. Down here I find pollution is the bigger threat to corals.

An article that portrays some hope need mentioning here:

http://www.linkedin.com/redir/redirect?url=http%3A%2F%2Flandscapesandcycles%2Enet%2Fcoral-bleaching-debate%2Ehtml&urlhash=28XJ&_t=tracking_anet

Hi Mike,

It’s great to see you posting again. Thanks a lot for the beautiful photos 🙂 – depicting terrible effects of Global Warming 🙁

If I may have a few questions please. On the topmost photos there are those greenish coral at the upper-right segment of the photo. Are that green stuff algae? And what are those brownish things among the clams and the white corals? Are they also corals or algae?

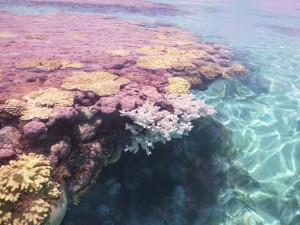

On the next photo, second from the top, I can see different growth forms. And only the branching one is bleached in the front. What about the pinkish and yellow-brownish ones? Are these colors, what we can see on this photo, the sign of suffering?

Are there any solitary corals at the bottom of the intertidal area? What about them, suffering too?

Do you have an idea about approximately how many different coral species are there in the intertidal area of your atoll?

And what about the corals over the reef crest, where they meet whit oceanic water?

Thanks Janos, I’ll sort out some other photos that show answers to your questions more clearly. For example, there are some green algae here, but not many; so we don’t have many fish that eat these species. Red algae is just starting to colonise the dead, and now the living, corals ~ so we may see a habitat shift: but not for the better. We have no seagrasses or mangroves; they never seemed to have crossed the Tonga Trench. In the Marine Biologist article you can see some cyanobacteria (blue-green algae): so that is colonising dead and now living corals, and growing over the bivalves too. When I put photos I’ll explain them in more detail. Until later, Mike

Here are some more revealing photos: the brown colour is the more normal for corals (small example in top right), the yellows are stressed, and then the white is when the dermal cells are discarded ~ removing the now ‘toxic’ zooxanthellae.

Here we see the blue cyanobacteria creeping across dead corals: this is not normally present. There is also some green algae, which is part of our marine flora, but is fairly rare. Different coral species are affected.

Janos: as yet we have no species inventory for corals ~ that’s on my list of priorities, but slipped down the list right now.

This photo makes it clear that not just branching corals suffer but encrusting corals too. I can see two clams but I’m quite unsure about their health.

Here’s a close-up of the cyanobacteria (blue-green alga). It looks quite beautiful, you can scrape it off with a fingernail, if it gets in your eyes it stings like crazy!

Given what I’ve just posted, I think you can now understand what is happening in this picture.

It seems the majority of branching corals have already bleached, I can see plenty of cyanobacteria and only one patch in the front which still has some brownish color, which is getting bleached too if I’m correct. The yellow-white at the bottom left has been stressed. Patches of green algae on earlier bleached corals can be seen too.

Right on the mark Janos, well done!

The main message here is that the pinks and yellows are normal ~ and are regularly exposed to high temperatures when low water occurs in the day time ~ these were the most resistant to hot water increases. Centre foreground is a clam ~ that died!

The corals beneath the overhang died ~ that tells me the warm water went right down to the lagoon floor, and that the deeper, or more shaded, coral species have a much narrower thermal tolerance and couldn’t cope.

Provided that this year’s El-Nino won’t be the new normal, and the recent heat-shock won’t be repeated yearly – as long as we live, we can hope – these stress-tolerant colonies probably can provide the atoll with future generations of corals. How much time does it take for a branching coral to grow 1 cm? in length?

Thanks Janos, that is the big concern: are strong El Ninos the new norm, and are even the La Ninas now going to become warmer? That is what the excellent Australian scientists are now talking about along the Great Barrier Reef.

I don’t know how long the branching corals take to grow, but that is certainly an experiment I can run for you. Simple way will be to nominate a few test specimens in slightly different water conditions (e.g. depth, lit or more shady side of a coral head, rougher or calmer directions) and then go back and measure them every few weeks. Nice idea, thanks.

The beautiful colour of a live pasua (we get various colours: blues, greens, yellows, purples etc.). You can also see the cyanobacteria spreading across dead corals, and the green ‘turf’ algae becoming more prominent.

So we had an immediate impact (coral bleaching & clam death), and now another impact starting (algal growth & colonisation), and may even have a longer term impact: change of habitat to algae and a shift in fish or bivalve populations. As I said: it is a ‘living laboratory’ on climate change impacts.

Well, in a ‘laboratory’ the person conducting the experiment is expected to be in control – in large – over what is going to happen. Whereas in your case you really witness and suffer what the industrial culture (aka civilization) brought to the ecosystem, don’t you? The clam looks beautiful though.

Haha! OK we need a new name. “Witness to the folly of humans destroying their own planet” seems a bit long though?

Moving on a bit: this is last week’s story from the southeastern corner of the lagoon ~ it’s much more exposed to wave action across the reef, and far less sheltered from prevailing winds (usually easterlies), Background shows a bare substratum and coral rubble from wave action. But, and here’s the problem, look what the red alga is doing. Growing rapidly over everything. Unfortunately I do not know if that was a normal plant locally (if so it was rare), or if it is an opportunistic coloniser from elsewhere? I’m unclear if we have fish that eat it.

Just so you can see the different type of habit. More rubble and more boulder type corals (porites), but the clams are just as dead.

But it seems there are at least same living branching corals. Anyway the overall picture is very sad.

Here’s my friend Ru Taime in the background, and at first glance it seems there might be some coral recovery. Look closely and the ‘brown’ is actually red alga all over the branching corals. Those little damselfish normally hide in the coral heads, I presume some sort of symbiosis: what will happen to them?

Ah, so was I wrong above by pretending living branching corals whereas there are beached one with red algae?

No Janos, you were correct. The earlier photos still had living, brownish, corals. The red algae is the next problem.

Sorry Janos, just realised you were talking about the rubble/porites pic. Yes those branching corals have red alga on them. (I just checked back on the original image ~ about 7Mb).

And just so you can see how quickly the red algae are growing over the dead (or still dying) corals. The lilac ‘finger’ in the left foreground is one of the colours stressed corals can go through. I’ll find another picture of this later.

In case you’ve forgotten what the atoll looks like. It’ll be easier for me to explain things in future too. Reef circumference is 77 km; lagoon area 233 km2. Prevailing winds usually easterlies.

OK, now we take a look on land ~ on the map above this is the long southwestern island, Mangarongaro, and about half-way down on the ocean side; Akasusa area. That ocean beach is the most important sea turtle (honu) nesting beach in the Cook Islands. The island is uninhabited so honu can lay their eggs in peace ~ no light or noise pollution, no wandering humans.

You can see that the forest is in a bad way. In recent years a combination of things has caused substantial tree loss: wave overwash, high levels of wind-borne salt, limited rainfall so trees can’t flush out the excess salt, increased solar and u/v radiation, and strong winds. As the outer trees fall down the inner, more-sheltered trees become exposed to the winds, but have less resilience ~ so they collapse too.

After a few months without rain all those creeping plants died too. Soil is then very dry and erodes through weathering.

And another photo. We’ve been replanting since May 2015. The big problem is a lack of shade, which makes it hard for saplings to become established. More on this in a moment.

This is more what the forest should look like. The ferns only like shadowy places; the spikey pandanus ~ centre right ~ are slow growing and OK in sun or shadow. A healthy forest is cool, the soil holds the moisture, and we have diverse habitats and species inside. Especially mosquitoes!

In April 2016 a professional photographer came by on a passing ship for a few days and asked if he could help with our research. He had a drone (quadcopter DJI Phantom 3) as part of his equipment.

So this is the view from the lagoon ~ and even from our boat you can see how degraded the far side is.

Here’s the site above with the drone flying north to south. You can see the honu nesting beach on the right and the leeward reef (ocean depth is then about 2000 metres). On the left is the lagoon, and then you get a pretty good understanding of how severe the tree loss is.

Please credit the two aerial images to: John Beasley, Dr Michael White, and Ru Taime, thanks.

Here we are flying east to west.

So why we are bothered about tree loss? The sex of sea turtle embryos is determined by the incubation temperature in the nest: more females are produced when warmer, more males when eggs are cooler. The process is called ‘Temperature-related Sex Determination’ (TSD for short). Eggs take about 2 months to hatch and the middle third is the critical period. Sex is determined by the proportion of time spent above or below the critical temperature (it’s around 29 Celsius). Once differentiated the embryos continue as either male or female ~ cellular structure is opposite so there is no going back.

Increasingly in our warming world it is becoming more difficult to produce male honu, and nesting projects around the planet are starting to report a female bias. So it’s one more route to extinction: species become single sex. There is evidence suggesting this was the mechanism that actually caused dinosaurs to become extinct. Crocodilians use the same process, but reversed ~ more males from higher incubation temperatures. Both sea turtles and crocodiles co-existed with the dinosaurs.

The photo shows a nest laid at the forest margin ~ it would be shaded during the morning hours.

What species are those trees behind the nest? Do you have an rough idea about the number of Honus visiting your atoll and laying nests?

Here’s a recent nest at Akasusa, you can see many trees have gone, so this nest now will be exposed to sunshine from morning to night. The sun sets to the right, so this beach is always very hot from about noon onwards, but previously it would have been shaded in the morning.

This is the reason driving our habitat restoration project.

What tree species do you plant for habitat restoration? Only coco palm?

Hi Janos, sorry for belated reply ~ internet crashed completely several times in June (usually for 24-48 hours).

I’ve attached the list of trees we use, some are fruit trees, most have medicinal value: but all are used in some way or another.

Where you asked about the trees behind the honu nest: those are pandanus ~ we have several species, one in particular is beautiful to eat. They can grow as a large bush, or as a tree ~ we use the leaves to make large mats, but the thorns are vicious.

So it seems the deterioration of the environment can be seen under and above the water too.

How do the people there react to all these adverse changes?

They are concerned, but also many islanders are interested in our research ~ I’m starting to see a shift and hope for very positive results in the next weeks. I’ll explain more as things happen.

On Tuesday 28th June I took Dr Teina Rongo (he’s the technical advisor for Climate Change in the PM’s Office at Rarotonga) & Kohe Taime (he’s our new climate change focal point at Tongareva ~ a local fellow) down to Mangarongaro motu to see all the tree-loss described above. I gave them a Tamanu tree to plant, and I put in another one too. These are slow-growing, but we’ve had them in planter bags for about 6 months, so we expect them to survive now.

Teina is a coral specialist and the government decided to charter a plane so he can visit all the northern atolls: they’ve all bleached in the last two months.

We then continued down to the southern lagoon areas and surveyed some corals. Many of the clams are recovering: water temperature fell in late-May: for the first time in five months. So the clams have taken in zooxanthellae again ~ hence the bright colours. We also found many new juvenile clams settled.

It seems that because our atoll and lagoon are normally pristine ~ we may get a very quick recovery. The situation on the Great Barrier Reef (& Heron & Lizard Islands) may be far worse, as they did not recover well last time round.

It’s great to see the clams getting bright. I have the same question I asked about the corals: For how long the clams can survive bleaching? As you wrote, temperature fell after a five month period, which is very long. It’s unbelievable that certain clams were able to survive. Do you have an estimation about their survival rate (% of species survived)? Maybe it is too early to ask, isn’t it?

Many thanks for the continuing update, it’s really great to follow the story. 🙂

Last point for today is that I’m using a colour chart to determine coral health. You match the nearest colour patch to the lightest and darkest points on your specimen. In this case most of the acropora has regained its colour, but there is still a patch of bleaching in the middle ~ so recovering, like bleaching, begins from the outside edges.

http://www.coralwatch.org

So it seems that bleaching does not necessarily means the death of the coral, does it? If they can recover, they are not dead. Is it fully understood why corals “expel” the algae – which make them so colorful – from their tissues? Have you conducted surveys to find out for how long can corals – various species, living in various depth – survive thermal stress after the bleaching has happened?

Have you surveyed corals living on the outside edge of the reef, where they meet with colder oceanic water – in contrast with those who live in the inner part of atoll?